Excessive Oak Junk - Huge Acorns (Round Fruits of Unusual Size)

- Ivy

- 17 hours ago

- 13 min read

Updated: 42 minutes ago

Ever seen a particularly large acorn, or other tree junk, maybe on vacation somewhere new or walking a new neighborhood, and thought- “Dang, that’s a big one!”? If you’re a plant nerd like me, then you said it out loud, picked up to show others, took pictures and then identified it and it’s in your collection on a shelf. This lead me down a wonderfully woody nutty nerd hole- Come along to look at huge oak junk acorns!

Yes, I have many trees’ nuts on a shelf, among other tree junk.< T.L.D.R buttons to skip to stuff >

Recall- oaks are in the Fagaceae plant family, with ash trees and chestnuts, and they are special partly for having their very own fruit name, just for oaks- acorns. That is the particular type of nut formed under a scaley woody cap/cup (the cupule) with a hard shell outside and tannin-filled seed inside. You know- what squirrels are always after if no one threw them peanuts.

Ok, I'll have to point out that some of the stoneoak (Lithocarpus species) trees, in the same

family as oaks, also make an acorn but theirs is harder (hence ‘stone' fruit) and not all species in the genus makes the acorn fruit. The monospecific genus of Notholithocarpus densiflorus or tanoak (only 1 species in its own newly categorized genus) also produce acorns but they are also harder (hence once being grouped with the Lithocarpus species, but are actually an example of convergent evolution not close relation). Thus the Notholithocarpus acorn shell is more like a hazelnut shell than true-oak Quercus acorn shell. The acorn cupule is also more frilly, finger-like than scaley though we'll soon meet some Quercus species with that too. I tell ya, it's a wild time in taxonomy!

Nevertheless- it’s the Oaks & their close relatives “Socalled-oaks” that have acorns. Cashews & pecans don't have these nuts.

It’s not easy to find on the internets (so you're WELCOME!), as most sites I came across are incorrect (probably AI-written), but the actual largest acorn on our big blue planet is NOT the Quercus macrocarpa (which does mean “oak large-fruit” in Latin). Those are indeed quite large and impressive with neat burred scaley acorn cups with a ring of fringe on top, because some oaks like to feel pretty.

Also called mossy cup oaks, we also know them as bur oaks and the acorns are about 3-4 cm (1-1.5”) in diameter & 3-7 cm (1-3”) long. Its leaves are also beasts at 6-12” long i.e. 15-30 cm. That is the largest oak acorn in the US and in North America, but not the largest of the western hemisphere or American continent or the world. Down to the south, in mountain & coastal forests stands a beastly beauty of an oak due for our admiration & protection.

Quercus insignis for the win in the nut contest!

The Quercus insignis (chicolaba, or encino bornio, roble blanco “white oak”) are native to Mesoamerica. They make acorns so big, that they mature over 5-10 years. That’s because they have to grow to about 8-10 cm in diameter (3-4”) & 3-5 cm (1-2”) long. Even the leaves reach 15-25 cm long (6-10”), though the trees aren’t excessively tall like a redwood but bigger than many oaks & even pine trees. That’s not the Quercus way anyways, they spread wide rather than going slim & tall.

The chicolaba oaks,Quercus insignis, get around 20 meters, maybe up to 40 meters in wet areas. That does slightly shadow its beefy northern sibling Q. macrocarpa, which grows to about 20-30 m (70-90 ft) in height. Fyi- Q.insignis is of the white oak group (North American oaks are grouped as either red or white, depending on the pointy or roundness of their leaves, and length of their acorns, with white oaks’ acorns maturing in a single growing season and red acorns in 2 seasons, plus higher in tannin content). Bur oak (Q. macrocarpa) is also in the white group of oaks.

The massive Q. insignis is a rare tree today but still abundant in Nicaragua and Costa Rica, and can also be found in Honduras, and Belize, but now rare in Mexica, Guatemala, and Panama, considered endangered in those countries.

Oak trees (and a few shrubs) species live across the middle of the globe in temperate deciduous and evergreen forests, subtropical forests, and both sub- and tropical savannas (the drier habitats).

More Huge Oak Junk Acorns -

Quercus lamellosa (bao pian qing gang, aka bull or buk oak) grows to 30-40 m (100-130 ft) and is native across India, Thailand & China at 1300-3000 m elevation, with evergreen leaves of 15-35 cm (6-14”) long and acorns clocking in at 2-3 cm long & 3-4 cm in diameter (0.75-1” long & 1-1.5” diameter). That's another chunky acorn. Their shape is similar to the bur and chicolaba oaks as “flattened”, like wide and squat with a short blunt point. Notably, their cupule holding the acorn has rings of frills like it’s in a short ruffled dress. WANT these!

Fun fact- Washington's only native oak species Q. garryana (Garry oak) is also among the top acorn contenders reaching up to 3 cm in girth. I indeed have seen some impressive plump Garry junk.Why so big? Benefits of being big in the cupule:

- 1st some background on Quercus breeding -

Oaks are not quick on the draw when it comes to reproduction. Slow & surprising is their style. The very common northern red oak (Q. rubra) will start making acorns scantily around age 25 and only really produce abundantly around age 50. This red oak takes about 450 days after pollination to mature their acorn fruits (reds take ~2 growing seasons, whites take 1). The also common eastern US white oak (Q. alba) has acorns (~3 cm / 1” long, ~1.5 cm / 0.5” diameter) that take 120 days to mature, with similar years taken to reach reproduction age. Once getting it on, oaks produce their bounty of fruits irregularly in quantity, being unpredictable to predators (squirrel!) and giving an advantage when they can occasionally produce so many acorns in a season the feeders are overwhelmed, letting more acorns sprout into the next generation of tree seedlings.

In other years, predation can destroy or at least damage 80% of acorns, or even 100% in low-production years (man, why even make any that year!?). OAKS SUPPORT WILDLIFE!

This large & variable fruit production is called Masting- and is synchronized across an area’s oak population. Fascinatingly, some have found instances where an extra old tree among younger oaks will mast offset from the younger ones, likely with the timing triggered genetically which has shifted over the generations. Masting may also be an adaption to help maximize pollination - reproduction on the pre-acorn end. It’s a massive pollen load sent to the wind in those years, making it more likely a pollen grain will land on the right & receptive oak stigma ("lady part landing pad") to fertilize the egg inside, thus making a bunch of acorn oak-babies. If ya don't time it right and all together, pollen can miss or land when the female flowers are not receptive.

Oak Life Lesson: Coordination helps you breed with your neighbors & overload your hungry enemies.

There are some 600 species of oak trees (and a few shrubs) across the world, and some have tiny nuts - acute acorns. The shrubby ones also tend to be on the petite acorn side.

Many acorns are a nice medium, enough for a nice squirrel meal. But a few are quite hefty in the hull, capacious in their cupule. Why get so big, especially since it is quite expensive to the tree in resources and time?

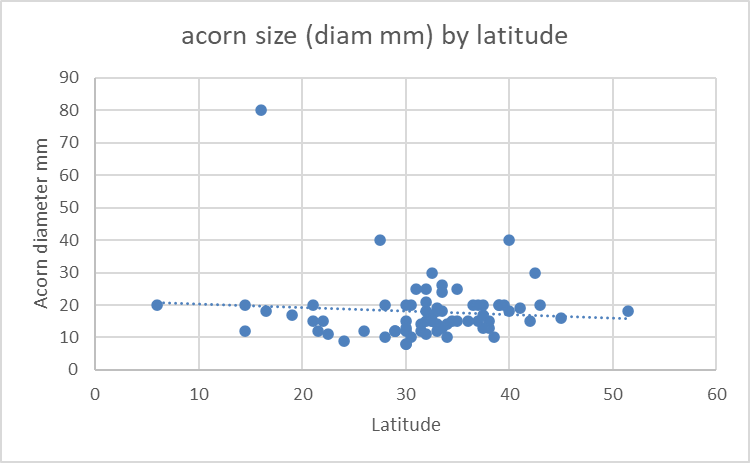

Generally and unsurprisingly, acorn size is influenced by water availability. Everything living (mostly) needs water. Drier habitats tend to support trees with smaller fruits & slower growth, so oaks adapted there have smaller acorns. This will even vary by species, with the same Q. rubra in a wetter area having larger acorns than one in a drier site. You also see a size gradient along latitude- acorns get smaller in the more norther areas of the north hemisphere (aka- decreasing acorn size with increasing latitude). This is both for same species and seems to be across species (remember the biggest acorn in in south Mesoamerica at low latitudes). That's because, simply, the growing season to plump up your fruits is shorter as we go towards the planet’s poles & longest at the equator.

Some oak species will also have acorn sizes & shapes (narrow or round) that help either distribute the seeds further from the parent tree but also have decent odds of surviving to make a new tree, or to not be eaten by the most common & small predator of the acorn weevil. Big acorns can’t be carried away and hidden by birds like jays who may not need to eat all their winter-stored acorns. So if you count on bird dispersal of your nuts, you want smallish/medium size & some will germinate if birds weren't struggling in winter. But extra small acorns will make you poor food for birds to disperse (not worth it) so they won't get far from big parent trees. but also are poor food for the plump weevils. So if weevil predation is high in the area, extra small may be the bet though ya may have your parents as neighbors.

That's small & medium acorn application. What about the huge'uns?

If the competition with other trees species to get growing space is high, like in more tropical (equatorial…wetter) regions, then slowly growing your seeds into massive acorns that can make a big radical for their first root and shoot up a taller first stem would be helpful to get a root-up on the competition. The North American bur oak is so large partly because its roots have to compete with dense prairie species that also make large root systems. Oaks generally don’t grow well in shade so the early seedlings need to shoot up quickly above the dense prairie wildflowers and tall grasses of the American mid-west.

Aw, like everything in ecology, botany, biology… there are several contributing factors: Water, growing season, distribution, competition & predation push the size of your nuts.

Let's get nerdier- hold onto your thinking cupules!

There are cases where other generally medium size acorned species will end up with some huge acorns. This has happened with Q. crispula, Q. gambelii, and Q. rotundifolia and happens when they basically get double fertilization either of a female flower duplicating the early embryo or its egg was reached by 2 pollen-tubes delivering their sperm cells. It's called polyembryonic fruit (normal embryo got copied in the seed) or polyspermic fruit (2 pollen grains reached 1 egg), thus creating acorns with an extra embryo inside thus maybe four instead of two cotyledons and two seed coats.

Basically- the tree made twins thus acorns bigger than normal!

Getting to smaller nuts-

We already know small acorns come from either oaks growing at higher latitudes (more northern, or even at higher altitudes up in the cold) or in drier areas. We often hear the fairly small Darlington oak (Q. hemisphaerica) as one of the smallest, running about 1-2 cm (1/2") long & 1.2 cm wide. The tree grows in the southeast corner of the US from Virginian into eastern Texas to about 15-18 meters tall. However, I found several smaller nutters at under a centimeter in diameter!

Both Q. ajoensis & Q. toumeyi run about 1.5 cm long and top at 8 mm wide. Q. toumeyi (Toumey oak) is a taller shrub oak of about 2-3 m while Q. ajoensis (Ajo Mountain shrub oak) is sometimes shorter from 1-3 m. Just above them is Q. franchetii (zhui lian li evergreen oak) is native to eastern Asia in China and Vietnam with acorns about 9 mm diameter & 11 mm long, growing as tall as maybe 10 m.

These ittybitty acorns however aren't making the shortest oak shrubs I found while researching over 73 species. Quercus vacciniifolia (huckleberry oak or Latin literally "oak of huckleberry leaf"), sprawls over dry rocky terrain at only about 0.4-1.5 m, 0.75 on average. The shorty shrubby oaks tend to be in dry habitats, no surprise. Acorns also small (~1 cm).

Evolution of Acorniness:

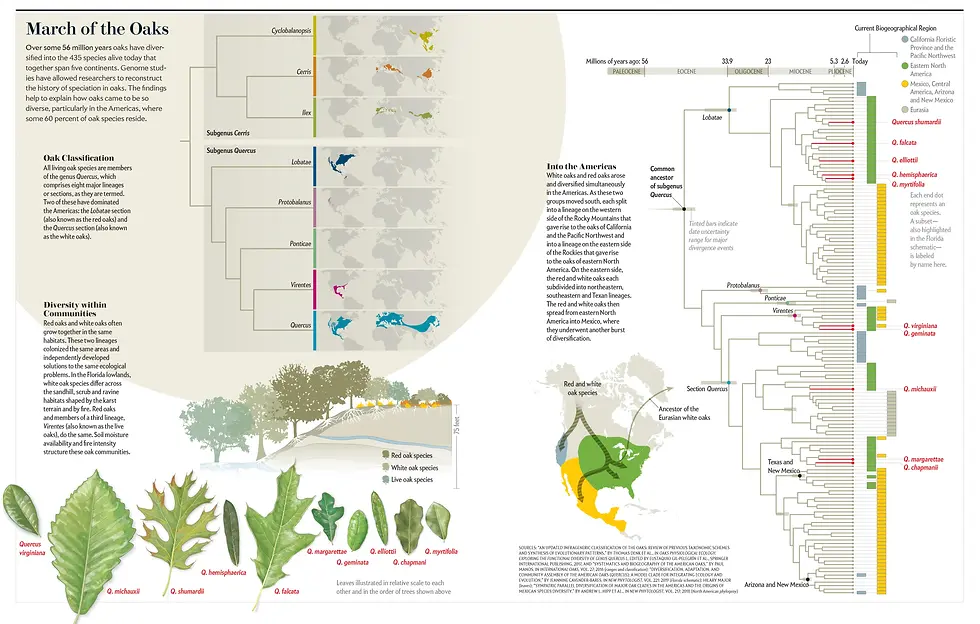

Today, oak distribution is predominantly North American, with 60% of the Quercus species

there. Yet the first fossil record entry for Quercus is as pollen dated to 56 million years ago around ancient Austria. But oak's ancestors of early Fabaceae family started in middle elevation tropical rainforests in Asia. Perhaps oaks began in Asia & west to the North American continent area OR ancestors became oaks in North America then spread back east before land-bridges were lost - hard to say as fossil records of plants aren’t complete.

However a fossilized acorn & cupule was dated to 48 million years ago from Oregon, USA ...

... supporting their spread first from the Asian land-bridge connection, as this lineage of oak still resides in SE Asia. These ancestral acorns belonged to evergreen trees and were generally larger, with modern deciduousness and smaller acorns evolving as the populations moved into drier areas across millennia. A common trait of the oak family, Fagaceae, that is also traced back to rainforest origins, is lacking seed dormancy and longevity. Very sadly, acorns do not store well even in the advanced seed preservation vaults, and it would be a very sad day in the future for our planet to lose all its oak species and future humanoids could not replant because no seeds could be saved. We’ll have tomatoes and aspen but oaks could slip away. Shudder to think! They are so hardy though, I think it could be oaks, fungi and cockroaches all hanging out on our graves.

There is a slight dormancy for a less-known black oak group (represented in my data by the afore mentioned small-nutted Q. hemisphaerica (Darlington oak). The black oak group has acorns that germinate in spring rather than fall-winter; a short dormancy & slight longevity. These species' acorns also give a valuable winter food source to local animals because they haven't turned into seedlings yet through winter. The delay however puts tender seedlings in safer temperatures emerging in spring rather than toughing it out through their first winter. Oddly enough, the so-named black oak Q. kelloggii is usually grouped with the red oaks group, yet it does have some seed dormancy through winter. Digging deeper, we see that the dormancy black oaks are actually a subgroup of the red oak subgenus, the ones with pointy leaves but have slight differences on top of the delay in germination. Oh the fun of taxonomy and phylogenetic trees, which I can stare at for sooo long, but that's my nerding.

Acorn Chemistry- nuts of plenty:

If you didn't know acorns are a valuable human food source, see my Pancakes Post.

Humans and our ancestors have been eating oak acorns for a long long time, with archaeological evidence indicating as many as 700,000 years ago in East Asia they were snacking away on these shelled oak fruits (An, et al. 2022). Most of the chemical component of an acorn is starch, sometimes making up over 50% of the nut’s dry weight. See why squirrels go nuts for... [No...sorry, that was too much]. Starch content varies widely among species, from 22% to 68%.

Acorns are also a good source of protein, fats, vitamins A & E, niacin, and minerals P, K, Ca & Mg, while famous even more so for their tannins (the compounds that “tan”/preserve animal skins and make acorns inedible unless removed). Always soak your acorns for long long time before eating or you'll preserve your insides & not in a good way. Acorns also contain monounsaturated fatty acids, sterols (known to help manage bad cholesterol), phenolic compounds (involved in giving plants their coloration & defenses, but also known for anti-inflammatory use in us) & tocopherols (Vit.E), which also exhibit antioxidant properties [8]. Acorns are also distinguished by their high mineral content, among which iron, zinc, copper, and calcium predominate [8]. In addition, the triterpenes found in acorns are potential anti-diabetic agents and may prevent liver fibrosis. Why NOT eat acorns?!

This has been a fun journey into the bigness (& smallness) of oak fruits, why they vary so much, their ancient origins, and a dash of acorn chemistry to wet the appetite.

Up next- Ancient Oak Specimens & Longest-Living Quercus Species (TBContinued.....)

You made it to the end, so here's more cool acorns!

References:

“The Nature of Oaks”, Tallamy, Douglas. 2021. Timber Press, Inc.

Redlist- Quercus insignis

Oaks of the World Quercus insignis

Successfully Growing Quercus insignis | International Oak Society

For Acorns, Size Matters—and So Does Shape | International Oak Society

Acorn Size: What Determines It and Why It Matters - Biology Insights

(PDF) Composition, Physicochemical Properties, and Uses of Acorn Starch

What Are Phenolic Compounds? A Detailed Explanation - Biology Insights

Oaks: an evolutionary success story - PMC -Phylogeny pic (Kremer & Hipp 2020)

(PDF) Systematic of Fagaceae: phylogenetic test of reproductive trait evolution – Phylogeny of Fagaceae pic (Manos, et al. 2001)

Phylogenomics reveals a complex evolutionary history of lobed-leaf white oaks in western North America - Quercus phylogeny

How Oak Trees Evolved to Rule the Forests of the Northern Hemisphere | Scientific American

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) | Hot Springs, AR - Official Website

Evolution and Subsection Classification of Section Cerris Oaks | International Oak Society

Latitudinal trends in acorn size in eastern North American species of Quercus

Comments